The fear of COVID-19 is real, largely because we are learning more about it as each day passes. This is also the primary reason it has devastated financial markets, which since the outbreak have experienced astonishing volatility. Not a single asset class has been immune.

As an Economist I am faced with a number of questions, some of which I have the answers to and some of which I myself am finding answers to. Having started my career as an Economist on the same day Lehman Brothers collapsed gave me a huge advantage, I began learning what the economic impacts of a global recession looked like on Day 1!

While that experience is certainly invaluable I also learnt there are events that can take you by surprise, just like this pandemic. The scale of this pandemic means we haven’t been tested on an extraordinary large scale like this before.

Here is a summary of some of the questions I’ve been asked:

What does the latest economic data tell us about the hit to the economy so far?

At the moment we lack official data post-COVID-19, the official data is from before the lockdown. We have had retail data for March released, which showed a 5% m-o-m fall in volumes, the biggest monthly fall on record. Despite the increase in food and alcohol purchases we do expect an even bigger fall in April with the closure of all non-essential stores.

So far the number of business closures and bankruptcies appear to be relatively minimal. The ONS Business Impact of Coronavirus survey (conducted between 23 March and 5 April), shows only 0.4% of the 6,171 businesses surveyed had ceased trading completely. A quarter of the businesses had reduced output while a surprising 75% were continuing to operate. Also encouraging was 35% of the businesses’ turnover was unaffected while 38% of the businesses’ turnover was substantially lower than normal. Similarly, the survey revealed only 0.4% of the businesses had made redundancies.

The PMIs for April are the worst on record with the composite index dropping to 12.9 in April, in comparison to the global financial crisis the lowest the index fell was 38.1 in November 2008. The latest PMIs indicate a quarterly fall in GDP of around 7%, but it is important to note that the actual decline could be even greater purely because the PMIs exclude the majority of self-employed and the retail sector. Additionally, the relationship between the PMIs and GDP may not be as significant as it would have during ‘normal’ periods. Nonetheless, if the PMIs remain unchanged next month then the OBR’s reference scenario of a 35% decline in Q2 will be an accurate reading.

What does the shape of the recovery look like?

V or not a V – that is the question!

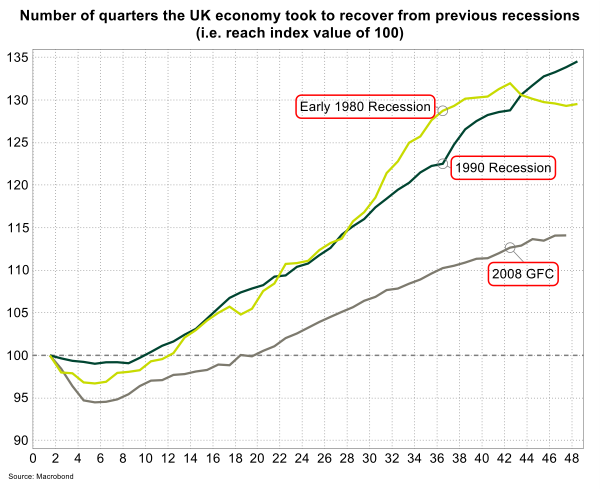

What can we learn from looking back at the previous three recessions? The early 1980s recession lasted five quarters, with GDP taking thirteen quarters to recover to pre-recession levels. The 1990s recession also spanned five quarters but took eleven quarters for GDP to recover to pre-recession levels.

The recent 2008 global financial crisis was the deepest UK recession since the Second World War taking 18 quarters to recover to pre-recession levels. But it is important to note the current recession was triggered by a health crisis unlike the three previous recessions. The previous three recessions had other structural problems such as banks taking on excessive risk. This crisis is different and if we get our policies right we will get out of this much quicker.

Our baseline scenario assumes the lockdown for the UK lasts about eight weeks before it is gradually relaxed. We expect business and household confidence to rebound once the shock fades. Thus GDP will fall by 6.7% this year, before recovering relatively sharply in 2021. There are a number of risks that impact this outlook.

What are the risks?

Most forecasters expect a swift recovery dependent on a sharp rebound in household spending. During the global financial crisis household spending fell by 5% over six quarters. During this pandemic we expect household spending to fall around 15% in just one quarter, this is also the reason why we are likely to see an unusually quick recovery. But there is a risk of a much weaker demand climate once the lockdown is lifted. A lower for longer level of consumption could deliver a protracted demand shock to the economy.

A further risk involves the re-emergence of the virus, which could lead to a re-introduction of the lockdown measures in the final quarter of the year. In this instance any policy measures that are implemented during this period may be less effective than during the first lockdown. Providing a larger hit to growth than before.

A bigger risk could be the hit to both demand and supply. This could be caused by ineffective policy measures that were unable to prevent widespread insolvencies and unemployment. Beyond short-term survival, some businesses may never recover.

And lastly, while most businesses have had to adopt and adapt to new ways of working almost overnight, these new ways of working may curb potential growth due to the reallocation of resources and capital.

How prepared were we?

I myself have referred to this pandemic as a black swan event – but come to think of it, it’s not the first time a pandemic like this has occurred. We had the SARS back in 2003, but on a much similar scale to this was the Spanish Flu dating back 100 years.

So why weren’t we prepared? I don’t have the answer to this one but a pandemic will now become a standard systemic risk. What I do think will be a big lesson out of this is how businesses build resilience. Systemic risks by the very nature remain a risk and cannot be eliminated; the risk can however be reduced by the way in how it is managed.